This is a brief comment on a recent article on the ageing of the diaphragm muscle (link to article here) by Bordoni, Morabito, and Simonelli (2020), along with some suggestions for how we might keep the diaphragm muscle strong, not just as we get older, but also in our younger adult years.

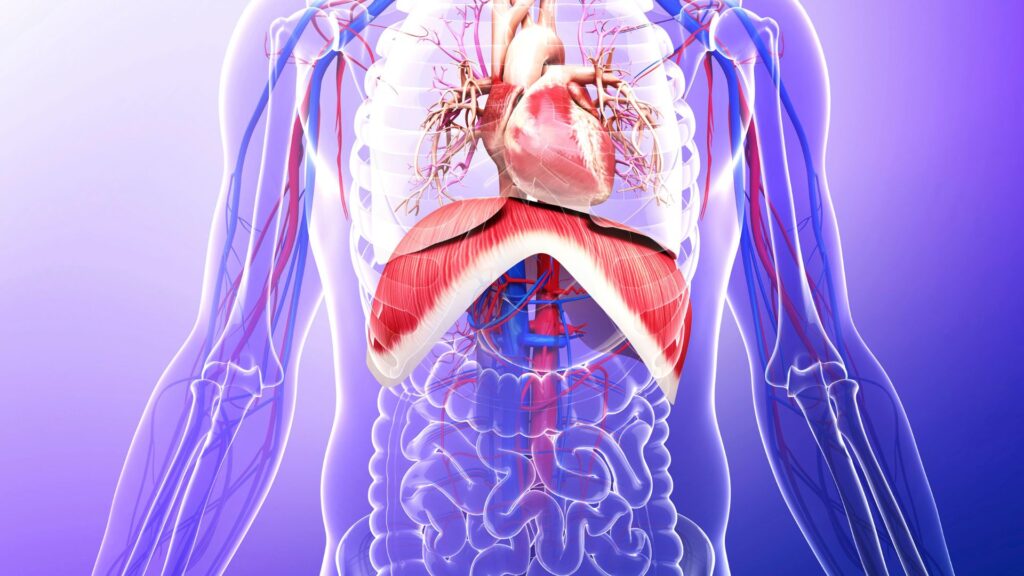

The authors of the paper comment that the diaphragm muscle is the most important contractile muscle used for breathing, and as with other muscles it is subject to ageing and sarcopenia (age-related loss of muscle mass). Their article discusses how the diaphragm muscles adapts to ageing along with other associated ailments and co-morbidities like back pain, emotional alterations, motor incoordination, and cognitive disorders, which – according to the authors, are related to breathing.

With ageing the diaphragm muscles becomes weaker and this can be associated with a person having difficulty cleaning the upper airways when coughing. The diaphragm can also become thicker with ageing as the muscle tries to repair weakening fibres, and this can cause balancing issues, an altered posture, weakening hamstrings and control of the lumber area. The authors also remark that a weaker diaphragm muscles means that the vagal nerve will not be able to communicate as effectively sensory information from the diaphragm to the brain, and those signals that do get through will not properly solicit emotional regions in a physiological way. This, they say, will potentially lead to changes in mood.

So, we can see from this research that it is crucial to keep the diaphragm in use for as long as we can. But how can we do this? One way is just to breathe with your abdomen.

By breathing abdominally you automatically engage the diaphragm as you fill the belly when you inhale and contract the belly when you exhale. Most of us breathe incorrectly and use the chest or thoracic region most of the time to breathe. Not only does this not exercise the diaphragm, it also activates the sympathetic nervous system and puts us into a state of fight or flight. Breathing with the abdomen, however, engages the diaphragm which increases blood flow to the region as well as stimulating the vagus nerve which is associated with activation of the parasympathetic nervous system. When the parasympathetic nervous system is activated we move ourselves towards a state of rest and digest and relaxation.

So, next time you get the chance, try breathing with your belly for 10 minutes or so. You can do this when you wake up in the morning, anytime during the day, or just before you go to bed. Once you’ve practised a few times, try to make abdominal breathing a habit.

Abdominal breathing is one of the key techniques used in pranayama and breathwork and you can find detailed instructions in the 5-day Breathwork Challenge.